U.S Online Gambling Laws

Key Points

- In the United States, gaming is governed by a patchwork of state statutes

- The Interstate Horse Racing Act of 1978 (IHRA) regulates horse racing wagering

- The Supreme Court struck down the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act in 2018

Is Online Gambling Legal in the US?

A simple direct answer is that gambling is legal in parts of the United States. However, US gambling regulation is a lot more complex, involving both state and federal statutes.

State legislature regulates gambling at the state level. These laws determine whether online businesses can legally operate and whether residents are permitted to gamble within the borders of each state.

Federal laws support state laws while helping to ensure that foreign and interstate commerce do not circumvent local laws.

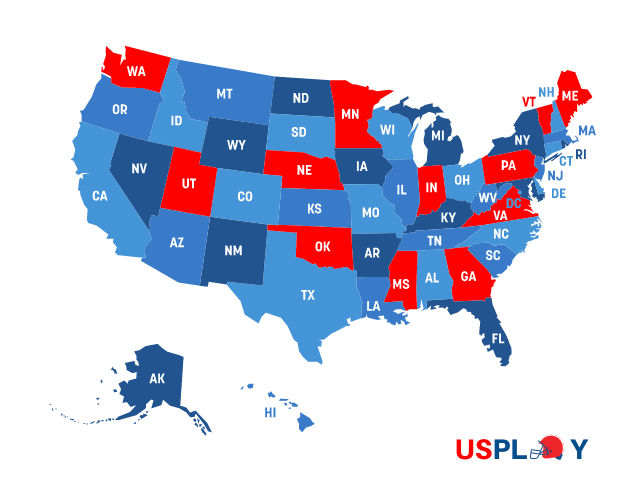

Some states, such as South Dakota and Utah, have laws that expressly prohibit certain elements of internet gambling or outrightly prohibit all of it, making it a misdemeanor or felony.

Others, such as New Jersey, West Virginia, Delaware, and Pennsylvania, have laws that permit and regulate online gambling activity only on approved, licensed platforms.

Legal Online Gambling

Gambling has a lengthy and complicated U.S history. Some types of it have been prohibited while others have been subject to more lax regulations.

Until recently, the federal Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act of 1992 severely restricted sports betting. The measure didn't outlaw sports betting, but it made it difficult for states that didn't already do so to pass similar legislation in the future.

In 2018, the Supreme Court struck down that federal regulation, restoring the authority of individual states to pass their own laws regulating sports betting.

The same may be said about online gambling. Running a gambling website in the United States is against the law as expressed by the Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act. However, this does not make it illegal for people to use the Internet to gamble.

As of 2023, daily fantasy sports (DFS) platforms and other fantasy sports leagues are not subject to the 2006 Act.

In the United States, gaming is governed by a patchwork of state statutes. The federal government generally defers to the discretion of individual states when it comes to regulating gaming. This implies that the legal status of gambling and the forms it can take differ across the United States. In 48 out of the 50 states, gambling is allowed, at least in some contexts. Utah and Hawaii are the only two states that outrightly prohibit it. Gaming is permitted throughout Nevada, which has earned a reputation as a gambling haven.

Gambling Laws By State

Read moreMost other states lie somewhere in the middle, such as those that restrict gambling to regulated establishments like casinos.

Additionally, several states allow some forms of gambling but not others. Bets on horse races, both on and off the track, as well as bets on sporting events and casino games, are all legal in states like New Jersey.

Bets on horse races are legal in Washington, but wagers on other sports are not. Moreover, in Washington State, casinos can only be found on Native American reservations.

Even if gambling is legalized at the state level, it may still be prohibited by specific municipalities. Local governments can opt out of hosting casinos and other forms of gaming.

What is the Federal Wire Act?

The Interstate Wire Act of 1961, also known as the Federal Wire Act, was enacted with the intention of suppressing organized crime by hitting the mob where it hurts the most: in the wallet. President John F. Kennedy signed it into law on September 13, 1961, and it remained unchanged for decades.

The Wire Act's original objective of stopping the illegal use of America's increasingly robust communications infrastructure to place sports bets across state lines was substantially achieved during the next four decades. Nonetheless, the rise of Internet gambling in the 1990s complicated the Wire Act's applicability. Attempts by the US Department of Justice throughout the Clinton and Bush administrations to expand the Wire Act's scope to include all types of online gambling, not only sports betting, resulted in a 2001 ruling that the law indeed covered all Internet gambling.

However, the issue was far from resolved. The Wire Act, as initially worded and interpreted by legislators and law enforcement for the better part of four decades, pertains only to interstate sports betting.

Regardless, the DOJ's ruling would stand until 2011, when the Obama-era DOJ changed its predecessor's position, and the dominant view was that the Wire Act only applied to wagers on sports.

In the following years, however, the issue surrounding the Wire Act has persisted, especially with the surge in popularity of paid-entry and daily fantasy sports (DFS) activities, which muddy the boundary between games of skill and sports betting.

Late in 2018, the Trump administration's Department of Justice once again revised its position, asserting that the Wire Act extends to all forms of casino-style gambling and sports betting. With New Hampshire leading the charge, states filed lawsuits against the Trump Department of Justice over its new interpretation of the Wire Act.

If you are active in the gambling industry or merely have an interest in it, or if you play on any of the authorized online casinos or sportsbook sites, you must comprehend the ramifications of the Wire Act for the future of sports betting and Daily Fantasy Sports (DFS).

In order to accomplish this, it is necessary to consider why the law was founded and what legal experts feel it does at present.

The History of the Wire Act

In 1956, US Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, the younger brother of President John F. Kennedy, initiated the process leading to the enactment of the Wire Act, which was part of a package of laws generally known as the Interstate Anti-Crime Acts.

Attorney General Kennedy believed that the mob's most lucrative industry was illegal gambling, not drug trafficking, prostitution, or any other criminal activities connected with organized crime.

Kennedy argued that the success of criminal groups in this field was largely attributable to their ability to utilize the nation's communications systems. Consistent advancements in telecommunications technology in the decades following World War II enabled racketeers to rapidly, easily, and frequently spread untraceable information about athletic events, enabling wagering on the winners before the results were generally known.

Just two months after being sworn in as Attorney General, Kennedy introduced a series of anti-racketeering legislation aimed at prohibiting the use of interstate telephone and telegraph connections for sports betting.

These recommendations would eventually merge into the Wire Act, which President Kennedy signed into law five years later.

Even though the Wire Act effectively reduced one of the major income streams utilized by professional criminals, it proved to be overly limited in scope. This is because it was only meant to help states in curbing illegal sports betting.

The Wire Act was eventually succeeded by more potent and effective legal instruments, such as the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO) of 1970. RICO combated racketeering by removing the gap that permitted crime syndicate leaders to go unpunished if they directed but did not actually commit crimes, such as rigging sporting events.

The Relationship Between the Wire Act and Sports Betting

After a period of relative anonymity, the Wire Act re-emerged into public discourse in the 1990s as Internet-based gambling became increasingly popular.

During the Clinton and Bush administrations, DOJ officials attempted to expand the Act's prohibitions to include all types of online gaming. Some members of Congress viewed the aforementioned 2001 DOJ pronouncement as a wholesale rewriting of the Wire Act, prompting them to repeatedly propose legislation that would rewrite the statute's original 1961 language. They desired to change the rules in order to expand the Wire Act's jurisdiction to the internet.

Technically speaking, such a step would be required if federal lawmakers wished to ban all online gambling, given the Wire Act was intended as a tool to combat organized crime, and gambling was not included in its scope.

Nonetheless, throughout the first decade of the 21st century, congressional efforts were undertaken to redefine the Wire Act's reach, disregarding the past congressional interpretation of the legislation and historical court decisions.

However, a key lawsuit involving the state lotteries of Illinois and New York from 2009 to 2011 turned the script once more, leading to one of the more recent interpretations of the Wire Act as legislation that only applies to sports betting and not all kinds of gambling.

In 2009, the Illinois governor's office and New York's lottery division requested an opinion from the Department of Justice regarding the legality of online lottery ticket sales and, more specifically, whether such sales would violate the Wire Act.

Over the course of the next two years, the DOJ's criminal justice division determined that the 2001 interpretation of the Wire Act was in disagreement with the Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act (UIGEA) of 2006.

The UIGEA eliminates intrastate transactions from its list of criminal online gambling-related activities, meaning no violation has occurred if a purchase is initiated and completed in a state where gambling is legal, even if electronic data briefly crosses state lines.

Even though it pertained to lottery ticket purchases and not Internet sports betting, the apparent conflict between the Wire Act and UIGEA prompted the DOJ's Office of Legal Counsel to offer an opinion on the subject in 2011.

Administrative law mandates the court system to defer to the government agencies entrusted with enforcing statutes when it comes to interpreting ambiguous laws, allowing the DOJ to render this ground-breaking ruling.

In any case, the 2011 DOJ judgment clearly eliminated any residual uncertainty over the Wire Act's scope: the statute would only apply to Internet-based sports wagering. Thus, governments such as Delaware, New Jersey, and Nevada were able to legalize, regulate, and tax various types of online gambling, such as the lottery.

Efforts to Reinstate the Wire Act

Nonetheless, anti-gambling forces in Congress have since pushed to institute a de facto federal ban on all kinds of Internet gambling via the Restoration of America's Wire Act (RAWA), which would alter the Wire Act to omit specific references to sports betting. Supporters of RAWA argue that their proposed amendments to the Wire Act are an effort to prevent the DOJ from reinterpreting laws without congressional consent.

If RAWA were to pass, interstate sports betting would be permanently prohibited. It is important to emphasize that RAWA was never written into law. In addition, the 2011 DOJ ruling is substantially closer to the Wire Act's original objective and the historical understanding of the Act's reach by Congress.

2019: Another DOJ Opinion Change

The 2011 DOJ judgment remained in effect for eight years, just enough time for a number of states to legalize and implement internet gambling, poker, and sports betting.

The Department of Justice, under the Trump administration, abruptly reversed its 2011 ruling and once again put major uncertainty into the burgeoning online gambling business.

Part Two of 2019: Judge Reverses The DOJ's U-Turn

Not surprisingly, the Department of Justice's sudden decision in late 2018/early 2019 to reverse its 2011 Wire Act opinion angered states and gaming operators who had relied on the 2011 interpretation to pass legislation and launch entire industries surrounding online lotteries, casino games, and poker.

In fact, the DOJ's new interpretation of the Wire Act stretched its scope even further than its pre-2011 understanding. The judgment jeopardized not only online lottery tickets and casinos but also the viability of existing multi-state lottery drawings that rely on interstate communications to run — even in states that do not sell lottery tickets online for those games.

The New Hampshire Lottery Commission (NHLC) filed a lawsuit against the DOJ over the decision, claiming it arbitrary, vague, and contradictory to the Wire Act's original plain text. Midway through 2019, a federal judge concurred with New Hampshire and issued a ruling reversing the DOJ's interpretations.

With the latest judgment, the Wire Act is now again interpreted as simply pertaining to sports betting. In the interim, states with online casinos and lotteries can breathe a sigh of relief, knowing that they are no longer at risk of significant disruption.

The DOJ could still appeal the ruling and potentially take the case all the way to the Supreme Court, but states with online casinos and lotteries are no longer at risk of serious disruption.

The DOJ replied to the judge's ruling by asking state attorneys general to defer all enforcement actions on the new interpretation of the Wire Act until "December 31, 2019, or sixty days following the entry of a final judgment in the New Hampshire case, whichever is later."

2021: Courts Rule In Favor Of Narrow Wire Act Interpretation

In January 2021, champions for online gambling won a significant victory when the First Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the lower court's ruling that the Wire Act only applies to sports betting.

The DOJ could have contested the verdict by requesting a review of the case by the US Supreme Court, but it chose not to pursue the matter. Thus, the restrictive interpretation of the Wire Act remains in effect: the Act applies only to sports betting.

What is the Wire Act's Purpose?

The Wire Act was enacted to aid states in implementing their separate sports betting and bookmaking laws in an effort to prevent criminal syndicates' unlawfully organized sports gambling activities, such as fixed bookmaking and matchmaking.

The law applies exclusively to unlawful gaming institutions, organizations, bookies, and other operators. Individual (or casual) gamblers, i.e., people who place wagers, who are unwittingly implicated in a racketeering scheme, have nothing to worry about the Wire Act.

This means that gamblers have nothing to worry about, but operators who are convicted face heavy fines and jail. Users of Internet sports betting services and platforms based outside the United States, such as offshore sportsbooks and lawful overseas betting sites, who are American do not violate the law because these websites are outside the Wire Act's jurisdiction.

To demonstrate that an operator is in violation of the Wire Act, the government must establish the following:

The operator accepted wagers for bets on athletic events from individuals based in other states.

The operator intentionally transmitted bets, wagers, or information facilitating the placement of bets or wagers (i.e., made the wagers available in some way) to individuals situated in other states.

The operator delivered a communication entitling the out-of-state recipient to receive money or credit for winning a bet or wager.

The operator utilized a "wire communication facility," which is described as any instrument, personnel, or services used or useful in the transmission of texts, music, photos, and sounds of all types by means of wire, cable, etc., which includes the Internet (albeit it did not exist in 1961).

What Does The Wire Act Say About Daily Fantasy Sports?

Technically, the Wire Act, which deals exclusively with sports betting (or at least is meant to), does not include daily fantasy sports (DFS) tournaments. This is due to the fact that DFS varies from sports betting in several essential legal aspects.

Given the prevalence of DFS in the Internet age, several concerns related to its legality have arisen in the last decade or so.

According to the prevailing legal opinion in the United States, playing DFS online, even for money, is lawful since fantasy sports is a game of skill, not chance, like sports betting. This legal distinction was explained in the UIGEA of 2006, but the gist of the law is that DFS is not considered a type of sports betting because:

A DFS player's athlete selections do not constitute the membership of a professional or amateur sports team.

All prizes and awards provided to winners in DFS contests are disclosed to participants well in advance of a game, and the amount of winnings is not reliant on the number of participants or any fees players pay to participate.

Winners are decided or at least indicated by the participants' knowledge and talent in selecting sportspeople with favorable statistics results following actual athletic events.

Money is not won in DFS contests by wagering on the point spread, the ultimate score of a single real-world team or combination of teams in a given sporting event, or the performance of a single real-world athlete in a single sporting event.

Despite what appears to be a clear distinction between DFS and sports betting, daily fantasy sports tournaments are not yet available in every state. That is not to argue that DFS participation is illegal in such places; instead, DraftKings and FanDuel don't want to take any chances given the confusing legal status of particular states regarding DFS.

Alabama, Arizona, Hawaii, Idaho, Iowa, Montana, Nevada, and Washington are the states where major DFS services do not let cash participants; residents of Puerto Rico are likewise prohibited from playing for real money in DFS games.

What is the Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act?

The Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act (also known as the Safe Port Act of 2006) is a law that governs the security of ports in the United States. It includes an online gambling provision.

The UIGEA prevents cash from being transferred from American financial institutions to online gambling sites, with the exception of fantasy sports, online lotteries, and horse racing.

As a result, many online casinos and poker rooms stopped allowing players or accounts from the United States.

The Act does not criminalize online gambling. It prevents financial institutions from funding accounts.

The Attorney General has practically unrestricted power under regulations governing Internet Computer Services (ICSs) to remove websites that they believe are in violation of the Act.

Origin of the Unlawful Internet Gambling Act

The process through which the Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act of 2006 became legislation generated much of the debate surrounding the law. The UIGEA was rushed through Congress as a "must-pass" bill just before a Congressional break, rather than after its pros and cons had been weighed and debated.

In other words, the UIGEA was attached covertly to a law that was already destined for passage, despite the fact that many Senators were unaware of its contents.

The Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act outlawed payment processing for unregulated online gambling. Gamblers may technically still place wagers on these sites, but they couldn't really make any financial transactions or cash out any winnings.

This bill's unfavorable impact was heightened by the fact that it was passed at a time when interest in online poker was skyrocketing owing to the widespread broadcast of Texas Hold 'em tournaments on television.

Sites that had built up a sizable client base of poker players were forced to make rapid adjustments or face the prospect of going out of business. As a result of UIGEA, online sports betting sites also experienced a decline in popularity.

However, the Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act of 2006's restraining influence has waned over time to the point that online gambling is prospering once more.

Two common forms of gambling, fantasy sports, and horse racing, have always been immune from this law. The UIGEA is seen as less of a danger by payment processors and online gambling companies now that there has been a widespread trend toward legalizing online gambling in the United States in recent years.

What Does the Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act Stipulate?

The Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act of 2006 stipulates the following:

- The law states that payment providers must block any transactions that they could prove were lined up for internet gambling.

- It also makes it illegal for online gaming businesses to process or receive user money. Companies that disobey these regulations may face prosecution in the United States. The site in question would have to reject the wager if the bettor placed it from a country or state where online gambling is outlawed.

- Third, the UIGEA attempted to define gambling but used vague language that may be interpreted in a variety of ways. From all accounts, the law's prohibition on "games subject to chance" was written specifically with the popularity of online poker in mind. Furthermore, the bill specifies that betting on sports is specifically prohibited on the internet.

Exclusion under the UIGEA

The UIGEA exempted interstate horse racing and lotteries, as well as fantasy sports. Additionally, any state whose laws allow some type of gaming is likewise exempt.

This implies that casinos in states like New Jersey, Delaware, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia that offer real money games can legally take deposits and pay out winnings to their customers. Under UIGEA, accepting credit card payments from a location outside of the United States is still illegal.

UIGEA and Online Sports Betting in the United States

At the time it was put into law, the Wire Act already governed sports betting and the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act (PASPA), which effectively prohibited sports gambling outside of Nevada.

In May 2018, the Supreme Court decided that PASPA was unconstitutional, paving the way for individual states to legalize sports betting. The Wire Act, which still expressly forbids the transmission of sports wagers across state lines, was unaffected by the verdict.

The repeal of PASPA has had no effect on sports betting, according to UIEGA. There are over 19 states and the District of Columbia that take wagers or have approved legislation to do so. The Wire Act still outlaws interstate sports betting, but UIEGA has no effect on modern sports betting.

UIGEA and Online Poker in the United States

Although the market for real money poker in the United States has grown rapidly since 2011, it is still a fraction of its pre-UIGEA size.

The legislation authorized the approval of regulated poker markets on a state-by-state basis. Consequently, West Virginia legalized online poker after the passage of the West Virginia Lottery Interactive Wagering Act in March 2019.

Players in New Jersey, Nevada, Delaware, and Michigan can all play against one another for real money because of a player liquidity-sharing agreement among the four states. Other states that could soon have the compact are Pennsylvania and West Virginia.

However, just a small number of states now allow players to wager real money on poker, so the online market is still a tiny fraction of what it was 15 years ago.

Although there was a brief period of growth in poker around the turn of the millennium, that boom has since died down. Even if all 50 states legalize online poker (which is unlikely to happen for a long time, if ever), it will likely never again reach the levels seen at the turn of the millennium.

There is little political will in most state legislatures to legalize real-money games like poker, and only five states have passed laws to regulate real-money poker, exempting UIEGA. Without federal interference, state legislatures may effectively repeal UIEGA, but this is highly unlikely.

What is the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act?

In the United States, Indian gambling is governed under the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act of 1988 (Pub.L. 100-497, 25 U.S.C. 2701 et seq. ), which lays out the legal parameters within which Indian gaming may be conducted. A federal gaming framework had not been in place before this act. The Act's Official Purposes Include:

- Providing a Legal Foundation for the Operation and Regulation of Indian Gaming; Safeguarding Gaming as a Source of Tribal Revenue;

- Promoting the Economic Development of Indian Tribes; and

- Shielding Tribal Businesses from Unfavorable Externalities (such as organized crime).

The National Indian Gaming Commission was founded and given regulatory authority by the statute. The statute also created new federal offenses that could be prosecuted by the Department of Justice and assigned additional powers to the U.S. Department of the Interior.

Legal Background of the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act

Tribes have been running high-stakes bingo and other gaming operations since the California v. Cabazon Band of Mission Indians judgment was issued in 1987. Frustrated by their inability to regulate tribal gaming, state governments had lobbied Congress for new legislation. This led to the passage of the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act in 1988. (IGRA).

IGRA legalizes gaming on "Indian lands" and creates a framework for governing this industry. Gambling is banned on any trust property acquired after October 17, 1988, with two exceptions: land purchased as part of a land settlement, land restored to a restored tribe, or the initial reservation of a newly acknowledged tribe.

The intent of the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA) was to provide a framework for regulating Indian gaming that would strike a balance between the interests of tribes, states, and the federal government in Indian gaming and allocate responsibilities for regulation fairly among all parties. There are three distinct types of Indian gambling under IGRA.

IGRA Classifications of Tribal Gaming

The IGRA defined three distinct categories for Indian gaming:

Class I

Games used for social purposes, such as traditional Indian games played at tribal festivals and celebrations. Tribes have exclusive regulatory responsibility over Class I gaming.

Class II

Bingo, pull tabs, and other games of a similar nature, including non-banking card games that are not forbidden by state legislation. Excluded expressly from Class II gaming are banking card games like blackjack and slot machines of any type. Under the jurisdiction of the National Indian Gaming Commission, tribes have the authority to regulate Class II gaming. Self-regulatory ordinances established by tribal governments require Commission approval.

Class III

All gaming activities not allowed in Classes I or II, including blackjack and slot machines. Class III games are only permitted on tribal lands if authorized by the governing body of the tribe, located in a state that allows gaming for any purpose by any person, organization, or entity, and conducted in accordance with a tribal-state compact between the tribe and the state where the gaming is conducted. Class III gaming compacts negotiated under the IGRA contain stringent provisions ranging from the application of criminal and civil laws regarding licensing and regulation of gaming to standards for the operation of gaming activities and financial assessments by the state to defray the costs of background investigations or other expenses incurred in the enforcement of the compacts.

As of December 2022, around 240 tribes in 28 states were covered by the IGRA.

What is the Interstate Horseracing Act?

Interstate Horse Racing Act of 1978 (IHRA) is a piece of US gambling legislation that regulates horse racing wagering across the country, including at off-track betting facilities (OTBs) and within the borders of the United States.

The law applies to individual punters, licensed online horse racing betting sites, and virtual horse racing betting services. Nonetheless, if you've ever wondered why online horse betting is so prevalent while other types of gambling are significantly less accessible via the Internet in the United States, the next portions of this article on IHRA should provide an explanation.

What is the Purpose of the Horse Racing Act?

The Interstate Horse Racing Act was sponsored in the United States Senate as SB 1185 in 1978 in order to regulate the practice of off-track betting (OTB) throughout the United States.

Before the regulation was implemented, off-track betting establishments were commonplace in both New York (where they started) and Nevada (which, as the mecca of gambling, ironically has no actual horse tracks of its own).

Without a federal framework, OTBs were causing issues in New York in particular, as small retail outlets sprouted up statewide, decreasing the gate at actual horse racetracks in the state. As a result, while wagering was growing significantly, tracks were losing money.

The IHRA, entrenched in 15 USC Ch. 57, mandates that OTBs distribute their earnings among themselves, the racetrack, horse owners, and the states in which they operate. Furthermore, any OTB would need specific consent from any track within 60 miles of its retail location, or the nearest track if outside of 60 miles (even extending into neighboring states). Individual state laws can levy varying fees and "house takes" on OTBs, and they can also decide whether or not to participate in the interstate horse racing betting sector at all.

What is Off-Track Betting?

Off-Track Betting, or "OTB" for short, refers to wagering that takes place away from official racetracks. To place wagers on horses without physically going to a racecourse, "off-track betting" has become increasingly popular. Betting on races in other states is also possible at OTBs, thanks to simulcast wagering (betting on live broadcast races).

So, a Floridian can use an OTB to wager on the Kentucky Derby, and the money will be transferred to their account as soon as the results are tallied. OTBs, together with simulcast wagering, make it possible for gamblers to participate in most horse races held in the United States from any location in the country.

As of December 2022, there were roughly about three dozen states with OTBs, including domestic off-track betting online.

What is Pari-Mutuel Betting?

One of the earliest kinds of gambling, pari-mutuel wagering, has been around for a long time. However, it is not "gambling" in the sense that casino games or sports wagers are. Because horse betting is considered a pari-mutuel industry, it is subject to its own set of laws that are distinct from those governing other forms of gambling.

Pari-mutuel is short for "pool-based betting," which is the simplest explanation of the concept. The original French meaning of the term is "mutual betting." While traditional gambling in the United States is defined by the fact that the house takes a cut of each player's winnings, the pari-mutuel system is community-based, and racebooks do not bank bets or assume any risk on their own.

At a racetrack or off-track betting facility, bettors can participate in parimutuel wagering, in which they can wager on a range of odds. The odds will adjust when wagers are received. The key takeaway, however, is that these odds are never set in stone until all wagers have been placed and the betting window has been closed.

The book then deducts its commission from the total, allocates the money to the various wager types (win-place-show, exotic, boxed, multi-race "pick," etc.), and calculates the final payouts. In other words, the payout for a pari-mutuel wager on a horse race is unknown until after the race has concluded and betting has been halted.

Horse racing betting sites only provide futures, which are house financed like sports betting futures, as a non-pari mutuel type of stake. These are not available through any U.S.-based online bookmaker, OTB, or racetrack.

Does The Interstate Horse Racing Act Legalize Online Horse Betting?

Yes, but not in clearly defined terms. The Interstate Horse Racing Act of 1978, which was passed into law before the Internet became a widely used commercial service, permits interstate online horseplaying in the same manner that the Interstate Wire Act of 1961 prohibits interstate sports betting.

In other words, the idea behind these rules has been extended logically to include the Internet. Therefore, since the Internet was developed as the development of that media distribution, the IHRA de facto applied to online wagering because the meaning of the Interstate Horse Racing Act was anchored in remote betting via media terminals.

However, states were required to permit this kind of horse wagering, and as of now, 41 have done so. The IHRA has no influence over the global online horse betting market or American residents' lawful right to gamble with these operators. As a result, US citizens may continue to participate in foreign racebooks (also known as international off-track betting sites) in all states (except WA, which bars all online betting).

Efforts at Amending the Interstate Horseracing Improvement Act of 1978

- Interstate Horseracing Improvement Act of 2011 — This was an effort to amend the Interstate Horseracing Improvement Act of 1978. However, the legislation offered by New Mexico Democrat Senator Tom Udall was unsuccessful.

- Thoroughbred Horseracing Integrity Act of 2015 — Representatives Andy Barr and Paul Tonko pushed another initiative by introducing the Thoroughbred Horseracing Integrity Act. The proposed legislation aimed to establish the Thoroughbred Horseracing Anti-Doping Authority as a separate entity. The Authority would be responsible for creating and implementing an anti-doping program for Thoroughbred horses (covered horses), trainers, owners, veterinarians, and others.

- Horseracing Integrity and Safety Act of 2015 — Representative Joe Pitt introduced the Horseracing Integrity and Safety Act of 2015 in the same year (the first HISA). Likewise, it failed to pass.

- Horseracing Integrity and Safety Act of 2020 — On September 29, 2020, Representatives Barr and Tonko introduced the Horseracing Integrity and Safety Act in the United States House of Representatives. Later, Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky introduced companion legislation that ultimately passed.

What is the Illegal Gambling Business Act?

The Illegal Gambling Businesses Act (IGBA), also known as the Prohibition of Illegal Gambling Businesses (18 U.S.C. 1955), is a federal law that was enacted in 1970 as part of the Organized Crime Control Act. The Act targeted syndicated gambling, or large-scale illicit gambling businesses believed to be funding organized crime.

According to 18 U.S. Code 1955, the government considers any firm that fits the following three conditions to be engaged in illegal gambling:

- It violates the laws of the state or political subdivision in which it is located.

- It involves at least five people who finance, own, or operate the enterprise; and it involves at least one person who is a public official.

- It operates for at least 30 consecutive days and generates at least $2,000 per day in gross revenue.

Penalties

Section 1955 violations are punishable by imprisonment for up to five (5) years and/or fines of up to twice the gain or loss associated with the offense, whichever is larger, or $250,000 ($500,000 for an organization).

In addition, the federal government may confiscate any cash or other assets utilized in contravention of the provision. Additionally, the offense may provide the basis for prosecution under the Travel Act, the money laundering provisions, and RICO.

Elements of a Claim

The elements of section 1955 apply to anyone who conducts, finances, manages, supervises, directs or owns all or part of an illegal gambling business that is a violation of the law of a State or political subdivision in which it is conducted.

It also involves five or more persons who conduct, finance, manage, supervise, direct, or own all or part of such business; and has been or remains in substantially continuous operation for a period in excess of thirty days or has a gross revenue of $2,000 in any single day.

Numerous courts have upheld the principle that Section 1955 prohibits any degree of participation in an illegal gambling business except as a mere bettor. As recently stated, conductors extend to individuals on lower tiers, yet with a function at their level vital to the illicit gaming operation.

Only businesses that engage in illegal gambling under state law and fall under the description of a business under the statute are prohibited. At the heart of any prosecution under this Act is the commission of illegal gambling, which cannot be pursued if the underlying state law is unenforceable under either the United States Constitution or the operative state constitution.

The business requirement can be achieved either by continuity ("has been or remains in virtually continuous operation for more than 30 days") or by volume ("has a daily gross revenue of $2,000").

The volume factor is very self-explanatory, and courts have been relatively lenient in evaluating continuity. However, they disagree on whether the jurisdictional five and continuity/volume characteristics must correspond.

Accomplice and Conspiracy Liability

Similar to violations of the Wire Act, Section 1955 offenses are also subject to the accomplice and conspiracy sections. It's a question of how deeply you're invested in each situation to make the distinction, which isn't always easy to do.

According to the statute, "to be guilty of aiding and abetting a section 1955 illegal gambling business… the defendant must have knowledge of the general scope and nature of the illegal gambling business, and awareness of the general facts concerning the venture… [and] [he] must take action which materially assists in 'conducting, financing, managing, supervising, directing, or owning' the business for the purpose of making the venture succeed. "before a defendant can be found guilty of aiding and abetting a violation of section 1955, a violation of section 1955 must exist… [and] aiders and abettors cannot be counted as one of the statutorily required five persons," which means that aiding and abetting is only prosecutable after the crime has been fully committed, unlike conspiracy.

Conspiracy under federal law is presumed to exist when two or more people plan to break the law and one of them goes ahead and does it. A conspiracy may exist even if one or more of the participants did not agree to commit or facilitate every element of the substantive violation. Partners in a criminal enterprise are jointly and severally liable for all criminal activities, regardless of how the work is divided up or who does what. The supporters are just as responsible for the crime as the offenders if the conspirators establish a scheme in which some of the conspirators commit the act while others provide assistance.

It is possible to be found guilty of both the substantive crimes of Section 1955 and the conspiracy to perpetrate those offenses because conspiracy is a separate offense. In fact, the Pinkerton doctrine holds conspirators jointly and severally liable for the conspiracy itself, the commission of the crime that serves as the conspiracy's object (if and when it is committed), and any other crimes that their co-conspirators could reasonably be expected to commit in furtherance of the conspiracy.

What is the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act (PASPA)?

In 1992, President Bush signed into law the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act (PASPA), often known as the Bradley Act. The bill, with a few exceptions, prohibited states from introducing legal sports betting. Oregon, Delaware, and Montana conducted sports lotteries were excluded, as were Nevada's permitted sports pools.

In addition, Congress gave states that ran licensed casino gaming during the preceding decade a one-year window from the start date of PASPA (1 January 1993) to establish laws allowing sports wagering.

Clearly, the latter exception was designed with New Jersey in mind. Nonetheless, New Jersey failed to capitalize on this opportunity. Jai alai, as well as parimutuel horse and dog racing, were excluded from PASPA's jurisdiction.

After a long battle between New Jersey and the major professional sports leagues in the case of Murphy vs. NCAA, the United States Supreme Court declared PASPA unlawful on May 14, 2018. The momentous judgment upheld a 2014 state law in New Jersey that allowed casinos and racetracks to offer sports betting across state borders. It also paved the way for every other state in the United States to follow suit.

Origin of PASPA

There is a lot of irony in the background of the law that was at the center of the seven-plus year court struggle between New Jersey and the professional sports leagues.

For starters, the bill was initially introduced on February 22, 1991, by Bill Bradley, a former professional player who had a stellar 13-year career in the NBA.

He did so during his time as a Democratic U.S. Senator for New Jersey (a position he held for three terms, from 1979 to 1997), during which he introduced the aforementioned legislation.

Former NBA commissioner David Stern, who testified at a public hearing before Congress on June 26, 1991, in favor of eliminating further development of sports betting, has recently come out in favor of at least amending the law.

Furthermore, had New Jersey taken advantage of a loophole allowed by the very legislation it has spent the greater part of a decade trying to repeal, the outcome of Murphy vs. NCAA (previously Christie vs. NCAA) would have been different in scope or unnecessary.

Rep. William Hughes introduced language to PASPA, giving his district, which included Atlantic City, 12 months from the law's implementation date to legalize sports betting within its casinos. In particular, the provision gave any municipality the option to introduce sports betting within a year if it has run casinos under a state regulatory framework within the preceding decade.

Atlantic City was the only other city in the United States (outside of Nevada) that met the criteria because it had a regulated casino environment for more than 15 years at the time.

Effects of PASPA on U.S. Sportsbooks

As a result of PASPA, wagering on sporting events became banned in nearly all of the United States. But it didn't mean gambling on sporting events was off the table.

For the 26 years that PASPA was in effect in the United States, illegal sports betting flourished on the black market, reminiscent of the booming alcohol trade during the Prohibition era.

To begin, it indicated a thriving black industry in sports betting. If you really wanted to gamble despite PASPA, you could probably find somewhere to do so, though it might not be with someone you can trust.

Online Sports Betting

With the introduction of online gambling, the dynamic once again shifted. Many American sports bettors used offshore-based internet sportsbooks in the decade leading up to the repeal of the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act (PASPA).

These sites were not entirely legit, unregulated, and rather risky to use, unlike the fully regulated sportsbooks that have sprung up in many states since legal sports betting was legalized.

There was a lot of under-the-radar illicit betting going on, as well as the more obvious black-market gaming. It was common practice for friends and coworkers to wager small amounts of money on games without fear of punishment.

The passage of PASPA outlawed sports gambling, yet many sports enthusiasts likely still gamble on a recreational basis regardless of the law.

Legal Matter in New Jersey

Over PASPA's 26-year existence, it was subjected to numerous judicial challenges. But Murphy v. National Collegiate Athletic Association was the most important of them.

The dispute dates back to 2011 when New Jersey held a non-binding referendum on whether to hold a vote to change the state constitution to legalize sports betting. After that, NJ governor Chris Christie signed a bill making sports betting legal.

This prompted a PASPA lawsuit against the state from the NFL, NBA, NHL, MLB, and NCAA. Despite considerable public support, the leagues ultimately prevailed, and sports betting remained prohibited in New Jersey.

By 2014, Christie had introduced yet another bill to explicitly challenge PASPA. The intent of the legislation was to make it legal to wager on sporting events in certain locations around the state. The state claimed it did not go against PASPA because it did not legalize sports betting but rather made it less illegal.

Instead, New Jersey contended that a specific provision of PASPA should be struck down because it violates the anti-commandeering principle, which, in layman's terms, bans the federal government from forcing states to conduct actions they do not want to take.

Furthermore, it was contended that the entire PASPA would need to be repealed if this provision were to be struck down.

The major leagues sued New Jersey again under PASPA, setting off a lengthy court battle.

Both the District Court and the Third Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in favor of the leagues throughout the subsequent years. However, on the 27th of June 2017, the Supreme Court agreed to hear New Jersey’s appeal.

US Supreme Court Rules on Sports Betting

A ruling was handed out by the Supreme Court on May 14, 2018. When New Jersey argued that PASPA went against the anti-commandeering principle, the Court agreed with them. In their verdict, the Court likened the action to placing federal agents in state legislative chambers.

The Court added that Congress would not have wanted PASPA's individual parts to operate independently, thus, the law must be interpreted as a whole. The court invalidated PASPA.

The Supreme Court has made it clear that while the federal government has the authority to regulate sports betting, if it chooses not to do so, individual states are free to enact their own laws. Sports betting is now legal across the country after being outlawed at the federal level.

After being prohibited at the federal level since 1992, states finally had the freedom to make their own decisions about sports betting.

The ruling did not immediately make sports betting legal throughout the United States; rather, it placed the responsibility for doing so squarely in the laps of individual states.

What is the Wagering Paraphernalia Act and Johnson Act?

The Interstate Transportation of Wagering Paraphernalia Act was enacted in 1961. The intent of the law was to criminalize the interstate transportation, except by common carrier, "of any record, paraphernalia, ticket, certificate, bills, slip, token, paper, writing, or other device used, or to be used, adapted, devised, or designed for use in" bookmaking, wagering pools on sporting events or numbers, policy, bolita, or a similar game.

This statute is intended to serve a very specific purpose. By shutting off gambling supplies, it "erects a considerable barrier to the circulation of certain goods needed in the conduct of various forms of unlawful gambling."

However, the following are not subject to the Act:

(1) Parimutuel betting equipment: These include legally obtained tickets and materials that were intended for use at racetracks or state-sanctioned sports betting events.

(2) The shipment of betting materials intended for use in placing bets or wagers on a sporting event into a state where that betting is authorized by the laws of that state.

(3) The carriage or conveyance of any newspaper or similar publication in interstate or international commerce.

(4) Tools, tickets, or materials used or developed for use within a state in a lottery administered by that state pursuant to state law.

(5) Equipment, tickets, or materials intended for use in a savings promotional lottery conducted by an insured banking institution or an insured credit union.

(6) The conveyance of foreign trade equipment, tickets, or materials intended for use in a lottery permitted by the laws of that foreign country to a destination in that particular country.

In the interest of clarity, the section defined the following terms:

(1) "foreign country" refers to any kingdom, nation, dominion, colony, or protectorate (other than the United States, its territories, and possessions);

(2) "insured credit union" has the same meaning as in section 101 of the Federal Credit Union Act (12 U.S.C. 1752);

(3) "insured depository institution" has the same meaning as section 3 of the Federal Deposit Insurance Act (12 U.S.C. 1813);

(4) The term "lottery" refers to:

(A) the pooling of profits generated by the sale of tickets or odds and the (B) random distribution of those proceeds or portions thereof to one or more chance takers or ticket purchasers;

(B) excludes betting on athletic events or competitions;

(5) The term "savings promotion raffle" refers to a competition where the only requirement for a chance to win specific prizes is the deposit of a set amount of money into a savings account or other savings program, where each ticket or entry has an equal opportunity of being drawn, and such competition is subject to rules that may from time to time be sanctioned by the relevant financial services authority (as defined in section 1002 of the Consumer Financial Protection Act of 2010 (12 U.S.C. 5481)); and

(6) The term "State" refers to a US state, the District of Columbia, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, or any US territory or possession.

Johnson Act

The Johnson Act, codified at 15 USC 1171 et seq., prohibits the shipment of gambling devices on a broad scale. The law does, however, permit shipping of gambling equipment to states or localities that have approved laws expressly exempting them from the Johnson Act's prohibitions. The Gambling Devices Act of 1962 clarified the types of devices covered and the reporting requirements for those who deal in gambling machines.

This section provides a summary of this law and its implications for interstate and international shipments of covered devices.

Covered Devices - Definition of "Gambling Device"

The Johnson Act restricts the shipment of "any gambling device" into any U.S. state or territory (i.e., Guam, Puerto Rico, etc.). 15 USC §1172(a) (a). A "gambling device" is defined as both assembled machines and machine parts.

(a) The term “gambling device” refers to:

(1) Any so-called “slot machine” or any other machine or mechanical device comprising a drum or reel, with insignia on it, as an integral component, and (A) which, when activated, may deliver, as the consequence of the application of an element of chance, any money or property,

((2) Any other equipment or mechanical device (including, but not limited to, roulette wheels and similar devices) created and produced primarily for wagering purposes, and (A) that when utilized could deliver, as a consequence of the application of an element of probability, any money or property, or (B) by the operation of which an individual may earn the right to receive as a result of the application of an element of chance; or

(3) Any subassembly or fundamental component designed for use in conjunction with such a piece of machinery or mechanical device but not connected as a constituent part.

15 USC §1171(a) (a). As such, the Johnson Act defines "gambling equipment" to encompass slot machines, mechanical gaming devices, and parts for these machines.

The Act excludes pari-mutuel wagering devices, fair crane games, and certain amusement devices from the definition of "gambling device" and thus from the Johnson Act.

Prohibited Conduct

15 USC 1172 prohibits the transportation of materials defined as "gambling devices" to jurisdictions that have not been exempted from the Johnson Act. This is due to the fact that the Act was written in part to help states and municipal governments in preventing gambling conduct, should such jurisdictions choose to regulate or prohibit gambling. Case law has determined that the purpose of the law is to prohibit the transportation of gambling machines; therefore, it is irrelevant whether the parties intend to use or operate the machines.

The prohibition applies to shipments made across state lines, as well as between local jurisdictions within a state. Therefore, as an example, although one county within a state may have exempted itself from the Johnson Act, a violation could occur if a shipment is made from that county to a different county within the same state that has not exempted itself from the federal law by state or local legislation.

The statute does, however, allow for transportation across non-exempt jurisdictions if the device stays within the shipping vessel throughout the voyage. 15 USC §1172(c) (c). Furthermore, case law has interpreted the law as not applying to shipments from the United States to an international destination.

The act also makes exceptions for various types of shipments, including those voyages occurring only in international waters, solely within a jurisdiction that allows use of the machines, and various types of shipments to or from Alaska or Hawaii. 15 USC §1175.

Manufacturer, Distributor, and Other Entity Registration and Reporting Requirements

Each person or entity that produces, distributes, sells, reconditions, or repairs gambling machines that affect interstate commerce is required to file the appropriate registration forms and materials with the U.S. Attorney General. 15 USC §1173(a) (a). This registration takes place annually. Employees of companies required to register are not required to register individually.

In addition, registered manufacturers must label each gambling machine with their name, the date of production, and the serial number. 15 USC §1173(b) (b). Any registered person or entity must also maintain monthly records of each device made or acquired, owned or held, and sold, delivered, or exported in interstate commerce. These records must include the name of the manufacturer, the serial number, the year of manufacturing, the device's location, and a description of the device. Additionally, the names and addresses of the buyer and seller must be documented. 15 USC §1173(c) (c).

Notably, case law has highlighted that those who deal in gambling machines only in jurisdictions that have implemented laws exempting them from the shipping prohibitions of the Johnson Act must nevertheless register with the Attorney General. See United States v. Various Gambling Devices, 340 F. Supp (ND Miss, 1972). Moreover, under the Act, a person or company that maintains gaming devices but does not run them must still register.

It is vital to highlight that the registration and labeling regulations also apply to persons engaged in foreign commerce, despite the fact that the act does not prohibit international transactions per se. Therefore, under the Johnson Act, a corporation that ships or otherwise transports gambling devices to another country must still register with the Attorney General and correctly mark the shipments.

Penalties for Noncompliance

Those who violate the Johnson Act, including the registration requirements, may be subject to penalties and/or imprisonment. The act stipulates that violators are subject to fines of up to $5,000 and/or imprisonment of up to two years. 15 USC §1176. Furthermore, law enforcement authorities may confiscate or seize gambling gadgets that are not transported in line with the law. 15 USC §1177.